Bland Ottawa needs a grand vision worthy of a national capital

The result is a city that lacks contemporary architectural beauty and a sense of purpose. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

In 2021, Ottawa city council approved a new official plan with a new vision for the city. This plan is very much reactive to current conditions, focusing on the not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) response that is prevalent in planning. It is also based on high expectations that council will take bold action to address growth, climate change and the housing crisis.

The official plan also enshrines the concept of maintaining access to views of nationally significant institutions such as the Parliament Buildings, but it is silent on how the public spaces around these buildings can be used, other than some broad aspirational goals for more pedestrian space. The recent trucker convoy and occupation of downtown streets show the urgent need to rethink the design of public spaces.

What’s missing in Ottawa is coherent design leadership.

Image: The post-Second World War Gréber plan, conceived as a grand scheme for an ambitious, growing country, is emblematic of Ottawa’s historic challenges. It brought the city pleasures such as the vistas surrounding the National War Memorial and turned rail lines, pictured here in 1903, into park trails along the Rideau Canal. However, it was also an engine of sprawl and questionable choices. Source: Library and Archives Canada.

We need a vision for how Ottawa and the National Capital Region become a place for people to live and to work; to celebrate and to mourn; to present itself on national and international stages as a city, as a capital and as a community. Ottawa needs to be both a city for people and city for the world, rising above the fractured nature of different government departments, jurisdictions and mandates.

This is not an easy process. But it is one that can be led by a design vision to identify issues, consider solutions and consult with people. We can present ourselves as Canada, the country, while creating a better place for people to live in the cities of Ottawa and Gatineau

But first we, as a city, must make some key decisions.

Take, for example, the LeBreton Flats. Since the 2016 implosion of two grand ideas centred around hockey rinks, the NCC is parceling off bits of the land to development projects. While a grand plan for the area was approved in 2021, completion is decades away, and the plan does not seem to consider the city as a whole.

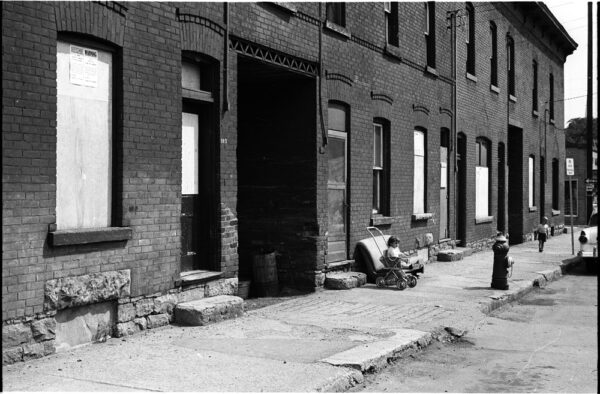

Image: The LeBreton Flats neighbourhood, pictured in 1963. The expropriation and destruction of the working-class neighbourhood – a largely vacant lot to this day – is a scar on the city. Source: Library and Archives Canada.

Image: LeBreton Flats pictured earlier this spring. Source: Miv Photography.

Nearby, Tunney’s Pasture is a complex of aged federal office buildings, many of which are at or beyond their end of life and in need of major investment. This was the NCC’s preferred site for Ottawa’s new Civic Hospital. However, only days after announcing this selection, the City of Ottawa and the hospital circumvented the process and proudly announced a different site with poor transit connections, contaminated soil, the remnants of foundations from former buildings, and unstable geology. While we destroy acres of much-loved greenspace for hospital parking garages, the preferred 121-acre Tunney’s Pasture site remains largely unused. A nearly decade-old proposal, incorporated into the new official plan, anticipates selling that land for development.

Municipal leadership is fractured and hampered by layered federal and provincial jurisdictions, security concerns and a post-COVID world of reduced office occupancy downtown. We have only to look at Sparks Street to see the challenges. What was once a thriving pedestrian street filled with shops, cafes and family-owned businesses has been largely depopulated due to a lack of leadership to make it a year-round destination for visitors and residents.

The ByWard Market is suffering a similar fate. As the second-most-visited tourist area in Ottawa, its once famed farmers’ market is largely gone: sellers of crafts fight for space amidst parking spots; brief attempts to make a pedestrian-friendly space were marginalized as pilot projects and then dismantled. A grand plan was commissioned, but largely ignored public input, seeking to establish a destination building in a privatized, for-profit, scheme for public land, while leaving unfunded the pricey nine-figure bill for public infrastructure.

Short-term solutions have turned Wellington Street into a pedestrian-only space. Temporary concrete barriers and checkpoints keep cars off the street, but we need more. Jersey barriers and temporary approaches aren’t fitting if our goal is safety, beauty and quality of life.

Image: Wellington Street, with Parliament to the left. Expanding the precinct beyond the ‘town and Crown’ line of Wellington Street is problematic. There is a historical precedent of separating the federal government from the city. While many incursions into city land have taken place, including the new temporary home of the Senate and the Prime Minister’s Office, we need to carefully consider where the town starts and the Crown ends. Source: Miv Photography.

The National Capital Commission, the “long term planner for federal lands” in Ottawa, has proposed ideas and solutions to address federal land use. But the NCC lacks funding for visionary goals, let alone for something as simple as keeping the prime minister’s residence in decent condition.

As well, there is the serious challenge that all of Ottawa is situated on the unceded territory of the Algonquin Anishinaabe people. Calls for reconciliation are meaningless without action.

Andrew Cohen summed it up well in The Globe and Mail when he wrote Ottawa is a city without imagination or ambition. More than a decade of municipal leadership has been about low taxes and paving more roads. Famously, Mayor Jim Watson tempered visions for the new light-rail transit system (LRT) being transformative by saying it is going to be “a great Chevy, it’s not going to be a Cadillac.” We can see where that went: delayed delivery beset by infighting and lawsuits, not to mention inquiries into contract awards that, famously, didn’t meet technical scores.

The blandness of buildings in the nation’s capital is partly the product of a federal government that doesn’t want to be seen to be spending extravagantly and a city government dedicated to low-fee, low-effort, mediocre design proposals, shying away from competitions to get the best ideas.

We also have a lack of architectural leadership. A new ministry of architecture or a city architect could provide guidance on important discussions, supported by a policy on creating better places for people. While an exciting federal design competition for new government office space has elicited grand visions, it has taken years to launch. The post-COVID work-from-home world leaves it with an uncertain future.

For the last 40 years, the Governor General’s Medals in Architecture have recognized the best architecture in Canada. It is telling that no City of Ottawa project has ever won. Only one federal building in Ottawa – the War Museum, by Moriyama & Teshima Architects, and GRC Architects Inc. – has ever won. By contrast, the City of Edmonton won one-quarter of the awards last year – largely led by expectations for excellence, embedded in design competitions, steered by a city architect. What we build is a sign of what we value.

The first could be a student stream, open to collaborative teams from Canada’s schools of architecture, with members from other disciplines, led by academic and professional guidance. Short-listed winners could be eligible for scholarships, publication and other rewards.

The second would be professional teams, including architects, planners, landscape architects, civil engineers and experts from other disciplines. Short-listed teams should be paid a fair honorarium, allowed to present and share their ideas, and hear feedback from the public and a professional jury. The best teams could finalize their submissions to create a short list for public engagement and more detailed design, selecting a finalist. That sort of visionary ideas competition helped create an inspiring vision for Sudbury for 2050.

Design competitions could help determine where light rail and bridges should go, and how to embrace the winter beyond snow-clearing budgets, looking at the aspirational goals we set for our society.

At a more detailed scale, competition entrants could look at specific sites or projects to tackle reconciliation, housing affordability and whether there’s room in the city for more museums. Specific projects can be explored to help address social equity and justice in a geographically disparate, ethnically diverse, language-rich community covering rural, suburban and urban environments across two provinces included in the National Capital Region.

The result of this process can be a guiding document that helps set goals. We can take small individual steps, knowing that they tie into a broader strategy.

We could choose, for example, to retain Wellington as a car-free street, but take immediate steps to make the environment more attractive and welcoming by adding trees, public washrooms and landscaping. We could integrate plans for urban development at LeBreton Flats with proposals to revamp Lansdowne Park, tying in improved transit within the core. We could take meaningful steps towards reconciliation through immediate actions embedded in the Truth and Reconciliation report.

Competition submissions could inspire new ways of thinking about mundane topics such as snow clearing and active transportation in a winter city. Ideas could be conceived at a high level and refined and explored at an intimate scale, showing that design and architecture affect our lives every day.

We can set a goal for ourselves, as a community and as a nation’s capital. We can choose to embrace a vision for excellence, where people and our sense of place matter, where we can realize our potential and show how we can prosper as a society, as a culture.

We can heal the damage caused by occupations, by lackluster visions, by challenging economic times. But we have to make that choice.

The time is now.

This article was also published in Policy Options.

Toon Dreessen is president of Ottawa-based Architects DCA and past-president of the Ontario Association of Architects. For a sample of our projects, check out our portfolio here. Follow us @ArchitectsDCA on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and Instagram.