Housing Potential Meets Political Will

In the heart of Centertown sits a parcel of land going to waste. Close to amenities like walkable shopping on Elgin, parks and the Rideau Canal and near plentiful transit options, 330 Gilmour Street is an example of wasted potential in the midst of a housing crisis.

This site is bordered on three sides by Gilmour and Lewis Streets to the north and south, and O’Connor Avenue to the west. An original structure built in 1922 served as the administrative offices for the Public School Board and was designed by William Caven Beattie who also designed the Crichton, Mutchmore and York Public Schools as well as many other notable structures in and around Ottawa.

Additions to the building were made in 1956 and 1963, respecting the character of the building and adding much needed functional space. For 27 years, Ottawa City Council used the Trustees meeting room of the building after City Hall (then at Elgin and Queen) burned to the ground.

But since 2001, when the land was purchased by Ashcroft Homes, the site has been derelict. The windows are boarded up and the site overgrown. Bits of the building have blown off in windstorms and some of the boards have come loose. The building is an eyesore and a poster child for demolition by neglect.

In 2020, a Carleton architecture student, Emily Essex, used the building as the basis for her thesis on community space. However no real, practical, solution has presented itself in the more than 20 years the site has been in private hands. This makes a strong argument for keeping public land and buildings in public hands: had public ownership been retained, it might not today be an eyesore. The case for continued public ownership, rather than selling public assets, has been made by many, including Carolyn Whitzman and the team with the UBC Housing Assessment Resource Tools.

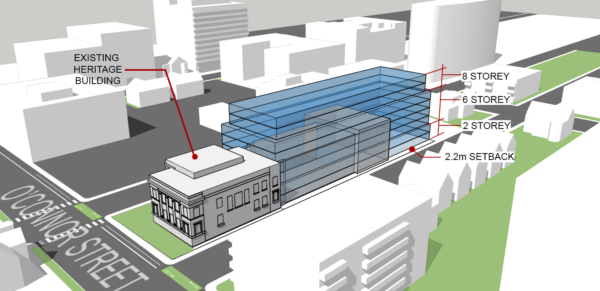

A 2007 zoning approval is in place for an 8 storey building but no steps have been taken to advance a creative use for the site.

Reviewing the detailed zoning permission for the site shows the enormity of the potential.

There is some argument to maintain the existing buildings. They form part of the heritage character of the area and contribute to the overall scale and community and are specifically called out in the City of Ottawa Centretown and Minto Park Heritage Conservation District Plan.

These additions may be in reasonable condition and retention would reduce landfill impact as well as maintain embedded carbon. This would also provide for about two thirds of the existing built form on the to remain, largely as-is. The 1956 and 1963 additions to could be adapted, including adding a few floors above the existing to provide some additional built form. However, the buildings are likely contaminated and may need extensive seismic and other structural upgrades that may not make for affordable homes.

Alternatively, we could look at only preserving the original 1928 structure. This would maintain the character of other similar heritage buildings on O’Connor and is a fine example of architecture of its era. While the later additions are interesting the original 1928 structure is, by far, the nicest part of the building.

Removing the 1956 and 1963 additions would create a potential site for development of a larger, more efficient, sustainable infill building. The original 1928 structure could provide approximately 1,500 square meters (16,000 square feet) of community and amenity space for the building.

Keeping only the 1928 wing would allow the rest of the site, as of right, to be developed with an 8-storey structure within existing zoning provisions. This would allow for a sustainable, carbon sequestered, rapidly constructed, mass timber, infill building with a minimum of impact on the community. This would also support Canadian technology and businesses, growing a demand for high quality, durable, buildings. The narrow site, regular floor plate and established zoning permissions make 330 Gilmour Street an ideal candidate for this type of project.

The resulting building could create approximately 14,800 square meters of new space (about 160,000 square feet). Taking 20% of this gross floor area for corridors, elevators, stairs and other unusable space suggests that approximately 11,800 square meters would be available for rent (about 127,000 square feet). That translates to approximately 170 homes, based on an average size of 750 square feet per home.

Obviously, this is a very high-level assumption; more, smaller, homes could be created, as could fewer, larger, family-sized, apartments. A more detailed design approach might land on just the right mix of unit sizes and configurations.

As well, a more detailed examination of the existing 1956 and 1963 structures might reveal that keeping them is feasible and cost effective. The current owner would have to provide a mandate to investigate and study this option.

This is a big ask: the developer is going to have to invest tens of millions of dollars of capital to construct this building and undertake this restoration. Not only is this project an $80-100 million project, but millions of dollars also have to be spent up front.

The City may need to offer some incentives for a shovel to hit the ground: the cost of construction; unknown, expensive planning approvals, and an uncertain financial market could be a big risk for the developer. But letting the site sit derelict devalues our community and undermines our goals for sustainable intensification. The continued deterioration of a heritage structure would undermine our goals to conserve and respect our cultural heritage.

These incentives could include:

-

– Granting planning approval in a timely manner: since the site complies with zoning and, other than a formal site plan application, there is little that the City can, or should, do to prevent the project from being approved within 2-3 months. Since zoning, setbacks, use and land use permissions are in place, granting site plan approval should be seen as a priority. Delays are expensive; a 2018 Report from the Ontario Association of Architects suggests that unnecessary planning delays adds $20,000 total economic impact per home per month of delay.

– Relieve the site from most vehicle parking requirements; the zoning bylaw requires 0.5 parking spaces per home, or at least 85 parking spots. The building is close to transit and amenities and is in a very walkable community. Both Gilmour and Lewis Streets have plentiful on-street parking for visitors and the streets are likely wide enough to accommodate temporary stopping zones for drop-off or delivery as well as protected bike lanes. A limited basement for accessible parking, services, (such as loading or garbage pick up), would save costs, allowing for a more sustainable, affordable, building. Below grade parking can cost in the range of $100,000 per space; requiring below grade parking, even at minimum rates, could add tens of millions of dollars in construction cost. Providing relief would set a precedent for Ottawa’s climate change objectives.

– Relieve the site from Parkland Dedication under a shared agreement to use the restored 1928 wing of the building as shared community space. A creative approach to the City’s Parkland Dedication bylaw would allow for this structure to be restored and redeveloped for public use and serve as a needed shared amenity space for new residents. This would enhance existing community spaces in the area, including the nearby Jack Purcell and McNabb Community Centres as well as Minto Park and other greenspaces in the area.

– Relieve the site from some of the required shared amenity space requirements. Developers are required to build amenity space for apartment buildings at a fixed rate of 6m2 per apartment; this creates games rooms, pools, party rooms and other spaces for the exclusive use of residents. For 170 apartments, the developer would be required to construct over 7,000 square feet of amenity space that must be maintained and operated. This adds costs that are transferred to residents in the form of higher rent or sale prices. That could be as much as $4 million, plus on-going operating expenses, none of which is accessible to the community and may never get used by residents. The restored 1928 building could be used as amenity space, shared with the community, helping to forge strong social bonds between new buildings and existing communities.

– Defer development charges for the project until after occupancy. Development charges for 170 homes could be $3 to $4 million. Deferral would allow an immediate capital investment in the project without needing the owner to pay cash out of pocket until the building starts to be occupied (and generate revenue) and provides working capital to the owner to invest in the community at no cost to the city. Further deferral until several years post-occupancy could create an additional incentive to aspire to a higher sustainable target like net zero or zero operational carbon, which requires greater up front capital investment. The debt could be registered on title to ensure payment is made before the property is sold or refinanced, ensuring the City is paid.

As part of the incentivization, the City could explore ways to contribute to the project and see value in trading off redevelopment of the site for benefits to the City: this could include securing some affordable housing in perpetuity or contributing towards heritage restoration.

The challenge of course is that this is a privately owned site, and the owner is fully within their rights to allow the site to decay or sit vacant. This is a glaring gap in municipal governance that other cities have tackled with aggressive vacant building bylaws. Winnipeg requires a permit for boarded windows with increasing costs for renewal; Winnipeg also charges an annual fee of 1% of the assessed value of the property. Based on publicly available data, if applied in Ottawa, that would generate over $40,000/year for the City and create a financial incentive to develop the site.

The challenge of course is that this is a privately owned site, and the owner is fully within their rights to allow the site to decay or sit vacant. This is a glaring gap in municipal governance that other cities have tackled with aggressive vacant building bylaws. Winnipeg requires a permit for boarded windows with increasing costs for renewal; Winnipeg also charges an annual fee of 1% of the assessed value of the property. Based on publicly available data, if applied in Ottawa, that would generate over $40,000/year for the City and create a financial incentive to develop the site.

If the owner will not be incentivized with a carrot, the City should be prepared to use a stick.

That could include, in the extreme, expropriation of the property for it’s current declared value ($4.1m according to City info). At that point the city could hold a design competition and award the winning team the right to develop the site, continuing to holding it as a public asset for public benefit or to be privately developed and owned. Similar design competitions in Edmonton resulted in dozens of creative design ideas from around the world, highlighting Edmonton as a good place to invest in design quality. That kind of creative thinking about architecture and city-building as both an economic tool and an act of physical placemaking is crucial design leadership we need to see in Ottawa if we are going to achieve our design aspirations.

We need bold action to tackle the urgency of the challenges we face.

We need to see value in engaging with the development community to take advantage of the numerous vacant parcels of land and derelict sites in our communities. We could meet many of our housing needs by thinking creatively about vacant, abandoned, and underbuilt properties. We have the potential to create sustainable healthy communities that make better use of transit, infrastructure, and community networks to achieve our municipal ambitions.

We need our political leaders to see the potential within our communities and engage developers, architects, engineers, and planners in finding solutions to our housing crisis.

Originally published in The CentreTown Buzz.